The United States just got a new X-ray laser toolkit to study nature’s mysteries

With a suite of reimagined instruments at SLAC’s LCLS facility, researchers see massive improvement in data quality and take up scientific inquiries that were out of reach just one year ago.

Some of science’s biggest mysteries unfold at the smallest scales. Researchers investigating super small phenomena – from the quantum nature of superconductivity to the mechanics that drive photosynthesis – come to the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory to use the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS).

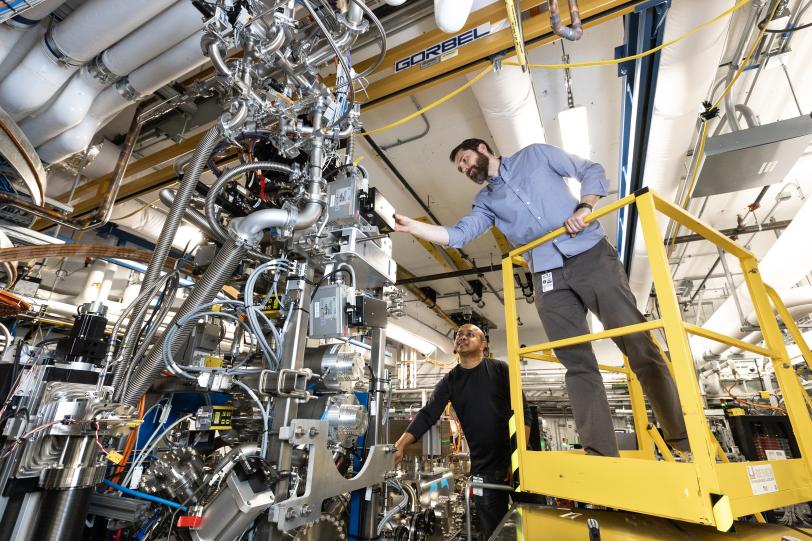

Like a giant microscope, LCLS sends pulses of ultrabright X-rays to a suite of specialized scientific instruments. With these tools, scientists take crisp pictures of atomic motions, watch chemical reactions unfold, probe the properties of materials and explore fundamental processes in living things.

After more than a decade of discoveries, LCLS got a significant upgrade – known as LCLS-II – that will ultimately increase its X-ray pulse rate from 120 to a million pulses per second. This about ten-thousandfold increase allowed scientists to reimagine their scientific toolkit, refurbishing existing tools and designing new ones to tackle questions that had previously been impossible to address.

SLAC senior scientist and TMO instrument leadThis upgrade marked a turning point – it has made previously impossible research possible.

Scattering X-rays

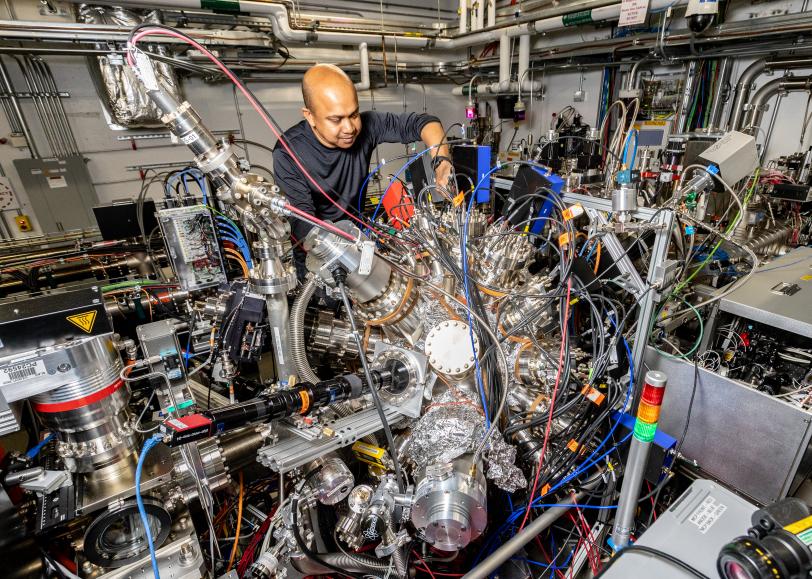

Two of these tools, the qRIXS and chemRIXS instruments, use a technique called resonant inelastic X-ray scattering (RIXS). With this method, researchers bombard a sample with X-ray pulses, exciting the electrons deep within, then releasing that excess energy in the form of light. Researchers use this light to reconstruct the reaction and study a material’s properties in fine detail.

By their nature, RIXS measurements are very “photon hungry,” explained Georgi Dakovski, SLAC lead scientist and qRIXS instrument lead. Most X-rays are absorbed or deflected away from the detector during experiments. For every billion photons that hit the sample, only one will reach the detector. “With the original LCLS pulse rate, capturing just a handful of photons was a work of art. We had to wait a long time to collect enough data for meaningful results,” Dakovski said.

But now, LCLS produces between 100 and 10,000 times more X-ray pulses every second. RIXS measurements that once took days now yield results in minutes or even seconds.

“The increase has already made an amazing change,” Dakovski said. “Not only is the data coming in faster and with clarity we haven’t seen before, it actually helps us see how the materials are transforming over time. We can watch how energy flows through the material and how the atomic components interact. We can create frame-by-frame ‘movies’ of the dynamic processes. This is only possible due to LCLS’s increased X-ray pulse rate.”

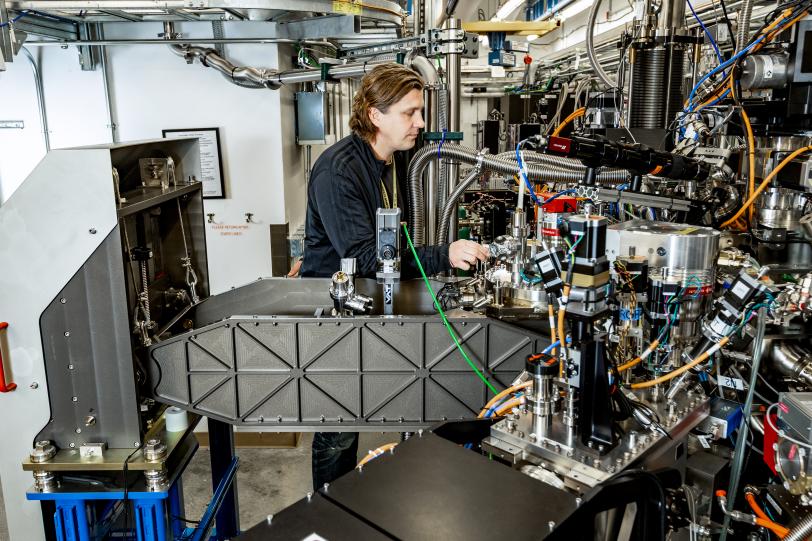

The upgrade made it possible to debut qRIXS this spring: a hulking instrument featuring a 12-foot spectrometer that swivels 110 degrees. The tool uses RIXS to investigate the quantum dynamics of solid crystalline materials. While its size allows scientists to examine a material from multiple angles with exceptional resolution, it also requires a huge influx of X-rays to produce quality data. These capabilities have long been on the LCLS user community’s wish list, but its high demand for photons made it impractical until now.

Today, researchers are using qRIXS to study materials like high-temperature superconductors, which transmit electricity with zero energy loss. Gaining a better understanding of the quantum phenomena behind superconductivity could help us design more efficient quantum computers, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) devices for medical applications and potentially lossless power grids at scale.

While qRIXS focuses on quantum materials studies, chemRIXS is tailored to analyze the chemistry of liquid samples, from ultrapure water to chemical solvents. chemRIXS provides researchers with a detailed look at chemical processes, such as the intermediate steps of photosynthesis, which could one day lead to the development of artificial photosynthetic systems.

Installed in 2021, chemRIXS had been gathering data on the LCLS beamline for several years before the LCLS-II upgrade. Kristjan Kunnus, a SLAC staff scientist and chemRIXS instrument lead, said the surge in X-rays has transformed the research possibilities for this tool. “Previously, we couldn't investigate low concentration solvates, so we had to use higher concentrations that didn’t completely reflect the chemistry under realistic conditions,” Kunnus said. “Now, we can analyze the diluted samples that matter in chemical applications and still get high-quality data, which just wasn’t possible before.”

Exploring atomic and molecular reactions

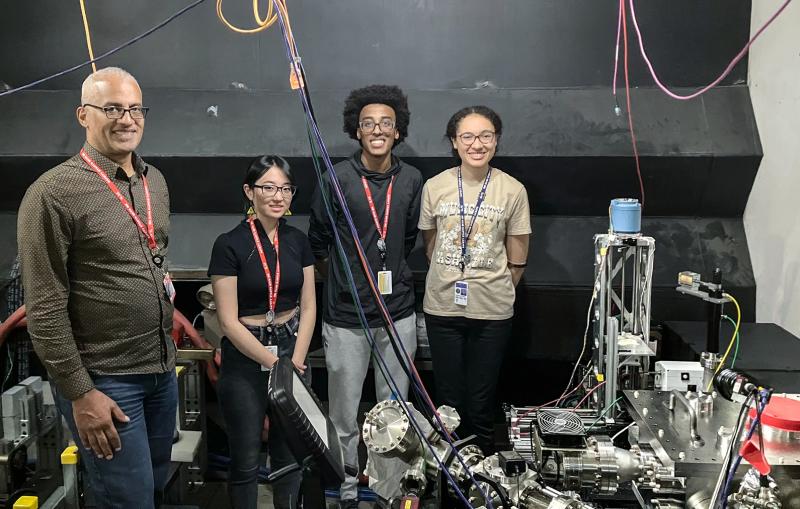

In the Time-resolved Atomic, Molecular and Optical Science (TMO) end station, several new instruments are leveraging the LCLS-II upgrade to study how electrons kickstart processes in biology, chemistry and materials science.

One of these instruments, the Multi-Resolution Cookie Box (MRCO), features a circular array of 16 electron detectors designed to take full advantage of LCLS’s increased repetition rate. Pairing this state-of-the-art system with LCLS ultrafast laser pulses, researchers can pinpoint the moment at which an electron is ejected from a molecule. They can also measure the energy spectrum and angular distribution of ejected electrons with extremely high precision. Together, these measurements help researchers understand how charge and energy is transferred in molecular systems on their natural timescales: just a millionth of a billionth of a second. Ultimately, this research tests the limits of quantum theory and contributes to the design of better catalysts and more efficient fuels.

"We’re no longer limited by this narrow window we had to look through before," says Razib Obaid, SLAC staff scientist and MRCO instrument lead. "This upgrade broadened the window of what we can study in each experiment.”

Also new to TMO is the Dynamic REAction Microscope, or DREAM, instrument. As the name suggests, DREAM is a powerful reaction microscope that allows researchers to study individual molecules undergoing chemical change. DREAM focuses the X-ray beam on a single molecule, stripping away its electrons until it “explodes” and all bonds in the molecule are broken. The exploding fragments are then detected and used to reconstruct a highly detailed image of the molecule. By compiling millions of these images, researchers can eventually build a molecular movie of a chemical reaction.

“How do photochemical processes – like sight, like solar power, like photosynthesis – unfold? How does DNA funnel energy when it absorbs light? How does an electron move from one side of a molecule to another? This tool gives us insight into how these things work at a fundamental level,” said James Cryan, SLAC senior scientist and TMO instrument lead.

LCLS-II: Building the world’s most powerful X-ray laser

SLAC’s renowned Linac Coherent Light Source now delivers X-ray laser beams 10,000 times brighter with pulses that arrive up to a million times per second.

This groundbreaking technique relies completely on LCLS's rapid pulse rate. To fully capture a molecular reaction, researchers need to photograph it from nearly a million different angles, requiring several million X-ray shots. In 2020, the team built a prototype to demonstrate its capabilities on the original beamline. They spent a week taking data but only gathered enough to create a single frame of the molecular movie they hoped to compile.

“With the original setup, it would have taken years to fully understand a single reaction,” Cryan said. “Now that DREAM is operating on the upgraded LCLS beamline, we're getting an entirely new view of these processes. This upgrade marked a turning point – it has made previously impossible research possible.”

The enormous uptick in the volume of data being collected at LCLS is not only making entirely new methods of research possible – it is also generating massive data sets for training foundational AI models. Such AI models can help researchers gather data more efficiently in the search for new materials and aid operators as they tune beamlines in real time.

“This integration of AI technology is poised to transform the research landscape, facilitating accelerated scientific discovery,” said Matthias Kling, director of science and Research & Development at LCLS.

With its enhanced capabilities and new set of tools, the LCLS-II upgrade has expanded the breadth of research being done at LCLS. Researchers are currently sifting through data from initial experiments, with many more planned for this year. The discoveries made possible by these advanced instruments promise to deepen our understanding of the fundamental processes that shape our world.

LCLS is a DOE Office of Science user facility. Upgrades to LCLS and its instrumentation are supported by the DOE Office of Science.

For questions or comments, contact SLAC Strategic Communications & External Affairs at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.